interview with Trajal Harrell

by Evelien Lindeboom

This year, dancer and choreographer Trajal Harrell is the associate artist of the Holland Festival. His unique style is inspired by various dance traditions, music, history, fashion, and visual arts. Together with his radiant group of dancers and guest artists, he will present earlier works, as well as his daring new project Welcome to Asbestos Hall, where he will try to recreate the spirit of Asbestos Hall, the studio of Tatsumi Hijikata (1928-1986), one of the founders of butoh.

Welcome to Asbestos Hall is the grande finale of a long period of research you did on the traditional Japanese dance-theatre artform butoh, and its relationship to early modern dance and voguing dance tradition. Can you take us back to the beginning of this quest?

‘I had been making a series in which the fashion runway was my signature, and in 2013 I decided that I wanted to change my way of looking at the fashion spectacle. I got intrigued by some incredible moments in the early eighties, when Japanese designers had appeared for the first time in fashion shows in Paris. They had a big influence on the aesthetics: bringing a very dark, monochromatic, androgynous vibe that brought descriptions of Japanese butoh to mind, even though butoh was from the sixties.

You traveled to Japan?

‘I had always wanted to go there, and this gave me an impulse to go and investigate whether Rei Kawakubo, head designer of Comme des Garcons, had been influenced by  butoh. What I had not realized though, was that people there would take my questions very literally. So, whenever I enquired about butoh, they tried to convince me to go see the archives of Tatsumi Hijikata – one of the two founders of butoh, along with Kazuo Ohno. At first that seemed too traditional to me, but I soon realized I couldn’t refuse. When I went and watched some of those pieces from the sixties, I was stunned! It was an aesthetic that I had never seen and couldn’t quite grasp. I wanted to know what this was about, so I started a new research, addressing the theories of butoh with my own work. This turned into shows like Porca Miseria (2022) and The Romeo (2023), and now it will come to an end with Welcome to Asbestos Hall…’

butoh. What I had not realized though, was that people there would take my questions very literally. So, whenever I enquired about butoh, they tried to convince me to go see the archives of Tatsumi Hijikata – one of the two founders of butoh, along with Kazuo Ohno. At first that seemed too traditional to me, but I soon realized I couldn’t refuse. When I went and watched some of those pieces from the sixties, I was stunned! It was an aesthetic that I had never seen and couldn’t quite grasp. I wanted to know what this was about, so I started a new research, addressing the theories of butoh with my own work. This turned into shows like Porca Miseria (2022) and The Romeo (2023), and now it will come to an end with Welcome to Asbestos Hall…’

What does your research look like?

‘My research is like swimming in a river; I immerse myself in something until it becomes a maze and there is no way out. In this case, I spent time in Japan, I talked to people, dove into those archives, looked at photographs and videos, read books, I went shopping for costumes… I never aim to replicate anything. Usually there’s a tension that

triggers more and more questions to come up. In this case I was looking for the tension between butoh and early modern dance that opened new possibilities within my own imagination.’

Can you tell us more about this tension between butoh and modern dance?

‘Dance is about strength in so many ways. My group of performers is very outspoken as well. We are not shy to show ourselves, and there’s a lot of power in that. Through butoh, which embraces old age and decay as a part of life, I found that I want to talk about weakness. Having experienced weakness myself, I realized that we can also validate that part of us, acknowledge and honor it as a part of the human experience that needs to be seen. I don’t want people to feel alone in their pain or sadness. Fragility is not victimhood, it can be present at the same time as strength, and when I started combining the power of the catwalk with strong, confident fragility, it resulted in a very interesting, extraordinary mix. I want to show weakness as a fundamental quality that unites all human beings.’

How was this (tension) present in your works Porca Miseria and The Romeo, that were shown at Holland Festival 2022 and 2024?

‘There is no easy answer to say how it’s all related. Different layers arise as we discuss different ideas in the group, incorporate them with our bodies and then experience this imagining of our body in the context of a theatrical moment. It can be seen, for example, in a stumbling yet proud quality in the movements. Porca Miseria was about women who created unorthodox ways of dealing with their own power and challenged society’s expectations of who they were. In a way the figures that I chose, Maggie the cat, Medea and choreographer Katherine Dunham, all challenged our notions and our parameters of this idea of the modern woman. The voguing dance tradition uses the word ‘bitch’ as a title of honor. When making The Romeo two years later, I got a sense of survival; the will of people to survive. I tried to make a fictional dance that would feel as though

‘There is no easy answer to say how it’s all related. Different layers arise as we discuss different ideas in the group, incorporate them with our bodies and then experience this imagining of our body in the context of a theatrical moment. It can be seen, for example, in a stumbling yet proud quality in the movements. Porca Miseria was about women who created unorthodox ways of dealing with their own power and challenged society’s expectations of who they were. In a way the figures that I chose, Maggie the cat, Medea and choreographer Katherine Dunham, all challenged our notions and our parameters of this idea of the modern woman. The voguing dance tradition uses the word ‘bitch’ as a title of honor. When making The Romeo two years later, I got a sense of survival; the will of people to survive. I tried to make a fictional dance that would feel as though

it had existed throughout many historical periods, something that everyone in the audience might feel they recognize even though it is fiction. I wanted it to bring people together. I always aim to create a moment of togetherness.’

Is this also the reason that you are always on stage with your dancers, at times performing, at times observing?

‘As a choreographer I need to look at the work. At the same time, I still feel that fundamentally, the part that I enjoy the most, is performing. I don’t know if I will ever be the kind of choreographer who sits in the audience. I’m always trying to find ways to be inside and outside at the same time.’

Can you tell us something about Caen Amour (2016) and Sister or He Buried the Body (2021), two works that you made earlier in this period of research into butoh, and that will be shown in the Stedelijk Museum?

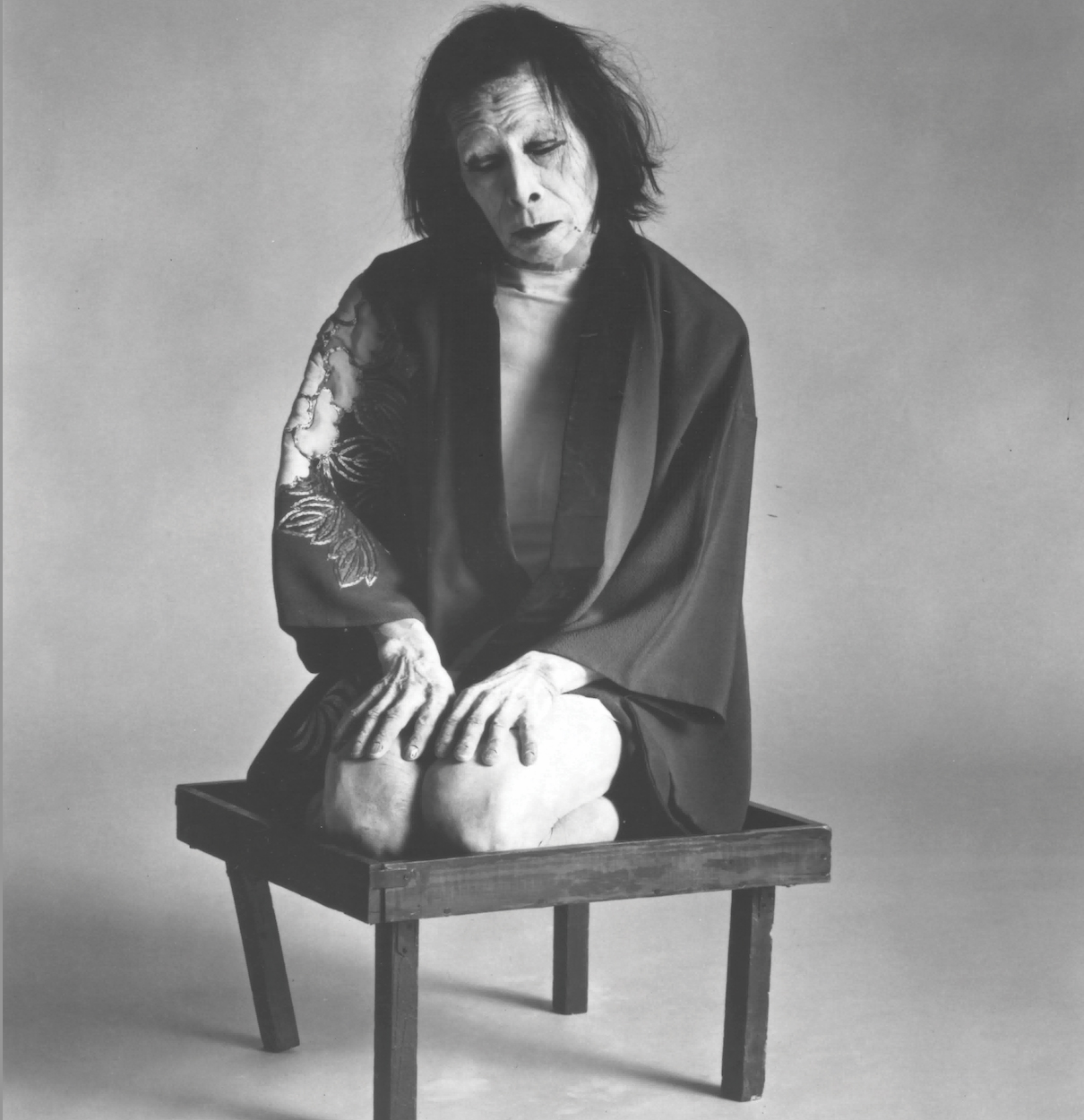

‘I am very excited they will both be part of Holland Festival 2025! Caen Amour refers to a period in the early 1900s, when women experimented with dance without having institutions for art dancing, breaking away from fixed ideas about burlesque entertainment, social, national or religious dances. They tried to make something that was artistic, and many were influenced by “oriental” dancing. This is where ‘hoochie-koochie’ dancing originates. This was historically interesting to me, and at the same time, I had vague memories of my father covertly going to such shows that triggered my curiosity as well. At the time of creation, I was moving a lot between theaters and art galleries, which influenced the perspective of the audience. The show is a culmination of all these things. Sister or He Buried the Body is a dance that, ideally, I will be able to dance until I am eighty, sitting down, using my hands. Including and representing older people is something that relates directly to butoh. This piece is my imaginative interpretation of an encounter between the ideas of Tatsumi Hijikata, pioneer of butoh, and the pioneer of Afro-American dances, Katherine Dunham. It should not be mistaken for a fusion; I do not do fusion dance. It’s my imaginative speculation from knowing they possibly met and shared a studio. I asked myself: how does that knowledge shape me as an artist?’

‘I am very excited they will both be part of Holland Festival 2025! Caen Amour refers to a period in the early 1900s, when women experimented with dance without having institutions for art dancing, breaking away from fixed ideas about burlesque entertainment, social, national or religious dances. They tried to make something that was artistic, and many were influenced by “oriental” dancing. This is where ‘hoochie-koochie’ dancing originates. This was historically interesting to me, and at the same time, I had vague memories of my father covertly going to such shows that triggered my curiosity as well. At the time of creation, I was moving a lot between theaters and art galleries, which influenced the perspective of the audience. The show is a culmination of all these things. Sister or He Buried the Body is a dance that, ideally, I will be able to dance until I am eighty, sitting down, using my hands. Including and representing older people is something that relates directly to butoh. This piece is my imaginative interpretation of an encounter between the ideas of Tatsumi Hijikata, pioneer of butoh, and the pioneer of Afro-American dances, Katherine Dunham. It should not be mistaken for a fusion; I do not do fusion dance. It’s my imaginative speculation from knowing they possibly met and shared a studio. I asked myself: how does that knowledge shape me as an artist?’

Let’s talk about Asbestos Hall. What exactly was this studio in Japan, originally?

‘It was the legendary studio of Tatsumi Hijikata (1962-1986), founder of Japanese butoh. It was known to be a very fertile place where artists would visit, hang out, sleep,

drink, make their own costumes – creating and talking all through the night. The pictures I saw were phenomenal. The energy of the studio setting is very different than a theater, everything is possible, there is a sense of experiment at the heart of it. They would, for example, wear their kimonos inside out. Many boundaries were crossed there, in good and bad ways. The bad being, for example, that some of the dancers would go out at night to make money doing erotic dancing and come back to donate some of their earnings to the studio. These things were never investigated, they were a given that would now be unacceptable. You cannot talk about Asbestos Hall now, about this highly reative productivity that was happening there, without addressing the other side. I’m not trying to present Asbestos Hall as this perfect monument of creative blossoming. There was an underbelly as well.’

drink, make their own costumes – creating and talking all through the night. The pictures I saw were phenomenal. The energy of the studio setting is very different than a theater, everything is possible, there is a sense of experiment at the heart of it. They would, for example, wear their kimonos inside out. Many boundaries were crossed there, in good and bad ways. The bad being, for example, that some of the dancers would go out at night to make money doing erotic dancing and come back to donate some of their earnings to the studio. These things were never investigated, they were a given that would now be unacceptable. You cannot talk about Asbestos Hall now, about this highly reative productivity that was happening there, without addressing the other side. I’m not trying to present Asbestos Hall as this perfect monument of creative blossoming. There was an underbelly as well.’

Welcome to Asbestos Hall will be a public encounter in a location called Likeminds in Amsterdam Noord. What will this nowadays take on Asbestos Hall be about?

‘To end this long butoh project in a studio setting is quite radical and celebratory, so that seems appropriate. We are going to spend a lot of time as a group. We will talk and rehearse there and present work that may be finished, that may be unfinished. We are going to play with time, like they did in Japan. We will also turn our kimonos inside-out, so to speak, because that’s what it feels like to invite people into your studio. A studio really shows the inside of the creative process. We’re allowing you, the audience, to come and see what goes on inside of us. It feels both terrifying and very exciting at the same time. I can’t say much about the outcome, but I hope that there will be different textures appearing, so that it will become a sort of collection.’

What should people expect when they come to visit?

‘The studio visit will not be a similar experience to visiting a big show. There may be some familiar elements, but overall, it will be more fast and dirty. More intimate. I think it will be very touching in its very own way: a new and heartful experience that requires some patience, willingness and maybe some forgiveness. There will be bigger and smaller creations, pop-up performances, late-night parties as well as guest artists that will arrange different kinds of experiences. We will provide forums for discussion and food for thought. One of the discussions will be about this legacy of Hijikata, including the darker side of his practice. His studio also had a problematic side to it, and he is available to be criticized. The audience can also expect us to include them, we will always provide a context for what we’re doing. At the same time, it’s super important not to spell everything out. If we want to experience something together, there is no point in predicting where we are going. The space to explore is an essential part of the artistic adventure, even more so in a studio setting.’

You talk about critizing Hijikata, even though he has been such a big inspiration. We are becoming more critical of the legacy of theatre and dance, when it comes to politics, visibility, violence and discrimination. What can we learn?

‘We must be critical; we can recognize that there are some people who obviously have a huge influence on history. But we need to address the ways in which they use their positions of leadership for their own positions of power. We are indeed really looking at those things now and that’s a good process. I’ve been super interested in big names in ance history, such as Kazuo Ohno and Katherine Dunham, but I think it’s healthy to be able to interrogate them as well. It’s important to bring our gods down to earth, take hem off their thrones. Humanizing them, seeing their humanity, makes us more human, too.’

You work with a steady group of dancers and performers. Can you tell me what this group means to you and how you work together?

‘There is a strong relation to the dancers. Some of them have been working with me since 2008, and there’s a group of younger people that started around 2017. So, there are already two generations with me, and that’s quite humbling. I could not have created all this work without them; it really is their work too. I respect them as artists, and I try to give them agency in the work. I think that’s important. Although we share a style of dancing now, I work with them in a way that makes them become more themselves, not copies of me. You know, it was a shock to me when at some point I had to realize that many young choreographers see me as the establishment now. I mean, I still worry. There is still a lot that I don’t know. I’m very glad that the dancers I work with also make their own work, and I hope I have a positive influence on that.’

The Holland Festival invites guests– artists who are also important to you. Can you tell us who they are and what they mean to you?

‘One of the guests will be my best friend from Tokyo, choreographer and dancer Takao Kawaguchi. We share an affinity and love for Kazuo Ohno and he will present a piece  about him. I am also very happy to bring choreographer and dancer DD Dorvillier to the festival. She is someone I met in New York, and I have a very long history with. She will do one of her pieces that I love, called No Change or “freedom is a psycho-kinetic skill.” And the wonderful musician Craig Taborn is joining us. This is a gift to me because he’s one of my favorite musicians in the world. If I had to describe his sound in one word, I would say it is speculative. I feel like his music is always searching. We’re going to do a blind date where I am going to improvise a dance to his live music. And there will be more guest artists.’

about him. I am also very happy to bring choreographer and dancer DD Dorvillier to the festival. She is someone I met in New York, and I have a very long history with. She will do one of her pieces that I love, called No Change or “freedom is a psycho-kinetic skill.” And the wonderful musician Craig Taborn is joining us. This is a gift to me because he’s one of my favorite musicians in the world. If I had to describe his sound in one word, I would say it is speculative. I feel like his music is always searching. We’re going to do a blind date where I am going to improvise a dance to his live music. And there will be more guest artists.’

What does this invitation to be associate artist for the Holland Festival mean to you?

‘First of all, I’m very thankful to Holland Festival for being so encouraging and supportive of my work, and this project unpredictable and doesn’t fit into standard expectations of results. The festival has made me a commitment as an artist already for years and this is a particularly great opportunity they are offering, to finish an era in such a unique way. It stimulates me to keep challenging myself. Being an associate artist is also interesting because I get to have this ongoing discussion with the artistic team about the festival itself, and they are open to my ideas and thoughts.It was a lovely process, to be a part of that discussion and the programming. I feel very included and enjoy it very much.’

What will it be like to be present in Amsterdam for three weeks?

‘Being present at the festival for three weeks, and create work in the studio, is going to be a pressure cooker. It feels like I am without my security blanket! At the same time, that honesty and openness is very human, so hopefully, people can relate. That’s the thing I’m betting on, that if we stay honest and generous people will want to reflect on what we have to offer, and value it for what it is. Being in Amsterdam means a lot. It was the first place I toured outside of the United States, and that resonates through the rest of my career. The attitude of the people here is very dear to me, I feel that dance is truly understood and appreciated here. The thing I love the most is being with the audience. This wonderful energy people bring, seeing the anticipation on their faces, is something I look forward to.’